- Home

- Jake Avila

Cave Diver Page 2

Cave Diver Read online

Page 2

Jacquie began picking up his discarded clothes and throwing them in a pile.

‘For God’s sake, Rob –’ she scrunched up her button nose – ‘this towel stinks. When did you last do the washing?’

‘I don’t know,’ he told her truthfully.

She looked at him closely. ‘Have you seen the front of the house recently?’

Before he could stop her, she’d pulled open the blinds.

‘Don’t –’ he began.

‘Fuck them,’ she snapped. ‘You’ve done nothing wrong. Stop behaving like a criminal.’

‘Jac . . .’

‘Look,’ she told him. ‘The grass is waist-high. It’s a firebomb waiting to go off. You want the council over, too?’

‘I’ve got to eat,’ he said, shutting the blinds again. ‘Do you want a cup of tea? There might be some milk.’

As he wolfed down the porridge, Jacquie expended more of her pent-up energy loading the dishwasher. Then, she made them both a cup of strong tea and sat down opposite him.

‘I know you never want to talk, Rob. But don’t you think you should? How long can you go on like this?’

He took another spoonful.

‘OK, so I’ll talk. Did you ring the bank? What’s happening with the mortgage?’

Jacquie followed his gaze to the letter stand by the phone. It was overflowing with unopened letters, many of which bore the Bankwest logo. Her voice trailed off in frustration.

Nash tried to say something and gave up. Since Natalie’s death, he had become increasingly inarticulate, as if the synapses that enabled conversation had been cauterised or withered away.

The clock on the kitchen wall was ticking off the seconds in an interminably slow motion. A great lethargy came over him. The ocean paddle had done its job. All he wanted now was to crash and forget. Why hadn’t Jacquie just come tomorrow as arranged? Inadvertently, he let out a loud yawn.

It was if he’d slapped her. Jacquie’s tanned cheeks flushed white.

‘You think it’s easy coming over here, knowing you can’t stand the sight of me? Wondering every day if you’ve managed to let the ocean kill you? Well, it bloody well isn’t!’ She was so angry she was shaking.

‘Jac . . .’ He was hopelessly inadequate in the face of her emotion.

‘Have you thought about how Mum and Dad will feel when you vanish?’ she interrupted him.

‘Look, I appreciate that you’re worried about me –’

‘Worried?’ she exploded. ‘Rob, we’re fucking terrified for you! It’s been a year now and as far as I can tell you’ve shut everyone out – friends, family, work . . . the whole bloody world. You haven’t been on an expedition since the accident. Hell, you haven’t been outside of Margaret River in six months!’

‘Look,’ he said firmly, ‘I am just trying to figure things out.’

Jacquie gave a shrill laugh. ‘And how long is that going to take? Face facts, you’re broke, Rob. The bank’s about to take everything and you’re just sitting here in a pile of smelly laundry. For God’s sake, brother!’ Her eyes flashed with contempt. ‘You used to follow your dreams and make them happen. Now you’re a shadow. A zombie. I can’t stand watching it anymore. It’s like both of you died in that cave.’

Her words thumped home like the well-aimed jabs they were. And because it was unbearable, he found himself lashing out blindly.

‘Why won’t you say her name, Jac?’

Her stare was incredulous. ‘You mean, Natalie?’

‘Yes,’ he snapped. ‘Natalie. My wife. The woman that everyone in this family seems so bloody keen to forget. Well, I can’t. And I won’t.’

Jacquie’s eyes widened. ‘Rob, I loved Nat like my own sister . . . Mum and Dad loved her, too.’ She reached out and gripped his hands. ‘You know that. What’s going on?’

Self-pity threatened to erupt out of him, and Nash fought hard to smother it.

‘Jac, I know you want me back the way I was,’ he said unsteadily. ‘But I’m not that person anymore. Can you understand that?’

She bit her lip. ‘Of course, I understand. And we’ve been waiting for you to heal in your own way, but it’s not happening. You’re stuck, and we can’t just stand by and watch you fade away.’

‘It’s gone too far,’ he admitted. ‘But you have to let me live my own life. OK? Hey, come on, please don’t cry, Jac.’

Jacquie was an intense soul, but the raw pain of her sobs as they hugged was unusual.

‘Is something wrong, Jac?’

‘I’m worried for you. For Mum and Dad. I don’t know how it’s all going to work out.’

‘What do you mean?’

Nash pulled back to stare at her thoughtfully. He knew her business empire was at that fragile point of equilibrium, where it would either soar or crash. And then there were his parents. He knew they’d invested heavily in the project, and they weren’t getting any younger.

‘Nothing. It’s nothing.’ She managed a smile. ‘I just love you so much. Please get some help and sort things out. If not for yourself, then do it for me. Please.’

He let her out of the front door and watched her stride determinedly up the path. Then she stopped and turned around with a laugh.

‘I just remembered why I came over. Uncle Frank is trying to get on to you.’

‘Uncle’ Frank Douglas was an old navy comrade of their father’s they’d known since childhood. Something of a rough diamond, he’d lived most of his adult life in Papua New Guinea, flying choppers. Nash had got him a contract five years ago on a major expedition in PNG with the Global Geographic channel, and they had worked on several projects until Natalie’s death.

‘What does he want?’ Nash was fond of the old roustabout, but he wasn’t in the mood to talk to anyone.

Jacquie rolled her eyes. ‘If you won’t answer the phone, then at least check your messages. He’s driving me nuts. Wants to talk to you about some cave. It’s all in an email.’

After watching Jacquie drive away, Nash went back inside and made himself a strong black coffee. Then he divided up the mail into three big piles and forced himself to look through it. Most of it was bills, final demands for electricity, gas, rates . . . some of them were dated six months before. With a guilty start, he realised they must have been paid by Jacquie or his parents. Then there were the letters from old friends, trying not to sound hurt at being cut off and offering support. There was plenty of hate mail, too. The most succinct simply read: ‘Fucking coward, hope you burn in Hell for what you did to that girl’. Finally, he got to the bank statements. The facts were stark. His credit cards had just been cancelled with total debts of 25,000 dollars. His 300,000 dollar mortgage was five months in arrears. The most recent letter from the bank was threatening foreclosure if he didn’t immediately make arrangements.

It was one hell of a comedown. For the last decade, Nash had shot documentaries with several cable channels and published three books. Until the accident, it had all been on an upward trajectory, and he’d been poised to rake in serious money. But, with his name trashed, the projects and the dollars had all dried up.

With a hollow feeling in his chest, he considered his options. He could sell the house, clear his debts, and walk out with a couple of hundred K in his pocket. But that felt cheap, like losing Natalie and his life all over again, so the question remained: what was he going to do?

Remembering Uncle Frank’s email, he plugged in the laptop. His screen saver was a shot of Natalie, taken on their wedding day after the guests had gone home. She was sitting on the deck, slightly tipsy, one tanned leg up, arms around her knee, just looking at him. The nakedness of her joy had always confronted him, even when she was alive. Some part of him couldn’t quite believe that he could have had that effect on someone.

The enormity of her loss threatened to derail him, and he opened the mail browser to escape her gaze. There were hundreds of emails. He found Douglas’s and opened it.

SUBJECT: You won�

�t believe this!

Rob,

Mate, do you ever check your phone? A TV outfit wants to shoot a major doco in a cave you’re very familiar with. Still hush-hush, but they’ve got the funding, chopper, boat, but they need a pro to lead the penetration! Your gear, your call, all expenses paid and a healthy fee to be negotiated!

Could be just what you need.

Get in touch ASAP!

Frank

Nash was struck by a word that Natalie sometimes used: kismet. Surely Douglas had to be talking about the Kaiserin Grotto?

Opening Google Earth, Nash clicked on the red place-mark pinpointing its location in the foothills of the Star Mountains, Papua New Guinea. Five years ago, he had mapped over three kilometres of submerged caves down to depths of 185 metres, before diminishing funds halted proceedings. He recalled soaring on his underwater scooter through a lost gallery of hauntingly beautiful calcite columns, towering like organ pipes in some vast cathedral. A product of ten metres of annual rainfall, the underground river ran on and on . . .

Nash sat back in his chair. Expeditions like this easily ran into the millions and took years to set up. By any measure, this was an incredible opportunity.

A familiar spark of energy flickered within him. The sensation was a precursor to that irresistible moment when the compulsion to seek and discover burst into a bright and implacable flame. A flame which could only be quenched by nothing less than all-out commitment to the pursuit and realisation of the goal.

Abruptly the spark sputtered and went out. Confused, Nash found himself staring blankly at the screen.

Chapter 2

Kebayoran Baru, Jakarta, Indonesia, three months previously

Leaving her lover sprawled in bed like a fallen colossus, Sura Suyanto wrapped herself in a silk sarong and padded across the mahogany floorboards to her 350-year-old Javan desk. Taking a seat, she opened the well-thumbed dossier. Although she had practised her pitch for weeks and committed to memory every detail of her momentous two-year quest, even a shuddering orgasm had not helped her sleep. It was hardly surprising. The man she was going to see was a dangerous and unpredictable foe, the second most powerful man in Indonesia. He was also her father and would spot any inconsistency in the story she was about to tell, so once again she prepared to tell it the best way she could.

Methodically, she ran through the maps, ledgers and historical documents, cross-referencing facts with scripted and memorised anecdotes, using skills she had picked up at Cambridge University and refined through ten years of top-flight investigative journalism. Only when the flowerpecker birds in the moon orchid grove outside her window trilled the coming of dawn, did she reach for the rosewood presentation box with her father’s carved initials embossed in pure gold.

Its contents had cost her a quarter of a million US dollars, and one awful night in Sydney with an obese collector of militaria. But this was a fraction of its potential value and well worth the sacrifice. Opening the box, Sura felt the same tingle of anticipation all over again. Dazzling against black velvet padding, the grinning death’s head badge and Knight’s Cross in pure silver gleamed as brightly as the day they’d been minted in 1941.

‘My lucky charms,’ she murmured, unnecessarily repolishing their faces with a fold of silken fabric. ‘Bring me good fortune, won’t you?’

There was a murmur from the bed, and Sura quietly closed the lid. Best to let Jaap sleep. When she needed to be focused and calm, he tended to provoke the exact opposite.

Inside the cavernous wet room, enormous jade tiles ran floor to ceiling, gold-plated tapware gleamed, and a bespoke porcelain bath emerged like a white lotus flower from the floor. Conspicuous consumption was intrinsic to the Suyanto dynasty. No matter how humble the object, it must dazzle and amaze. Not that this bothered Sura. The problem was it all belonged to him.

She punched in the shower code for her preferred temperature and flow and began washing in fine sandalwood soap. Her mother’s genetics – another astute purchase by her father – had blessed her with long legs, a waist Jaap could easily span with his hands, and full, pear-shaped breasts. Keeping that body looking fantastic was part of her job, and she ran thirty-five kilometres a week on top of doing free weights and Pilates. Sura Suyanto was twenty-eight, but she looked eighteen. Her symmetrical features and plump Cupid lips made her popular with her fifty-five-million-strong Indostar News audience, and something about her huge, widely spaced brown eyes created an impression of naivety, which inspired men to fancy they could realise their will in them.

How very wrong they were.

Jaap was sitting up in bed when she returned. The gigantic Afrikaner could have been carved from a block of white marble. A chiselled study in muscle, everything about him was oversized, except his intellect.

He asked how she was feeling while staring hungrily at her crotch.

‘I’m a little nervous.’ She slipped in to a demure grey kebaya, the kind her father approved of her wearing when she wasn’t on camera. ‘He can be unpredictable.’

‘Ah, once he sees what you’ve brought him, he’ll be putty in your hands.’

Jaap had never met her father, and if she had anything to do with it, he never would. Sura was dabbing perfume behind her ears when he grabbed her from behind. He was more than twice her weight, and his biceps were bigger than her thighs.

‘I want you,’ he said fiercely, his short beard tickling her neck. As her feet left the floor, she could feel him pressed against her back like an iron bar. ‘How about a quickie for good luck?’

‘Idiot, put me down!’ The hurt in his china-blue eyes reminded her of how immature he could be. ‘Wait for me here, and whatever you do, do not go outside. Do you hear me?’

‘Ja.’ He frowned. ‘I heard you the first time.’

Outside on the driveway, her father’s chief of security, Angka, waited impassive as a toad in a luxury Mercedes AMG. The driver was a soldier in civilian clothes. Behind them, another black Mercedes contained a heavily armed detachment of bodyguards. The drive took a few minutes. The general owned significant chunks of Kebayoran Baru and Menteng and preferred to keep his children close by. Tommy, his only son, lived in the biggest house next door, while Sura and her two older sisters, now both married, lived further along the road.

They drove beside an imposing white wall for a kilometre before arriving at a fortified gatehouse. Sura straightened her shoulders as the sentry approached the car. Dealings with her father were never easy.

Steel security gates silently swung open, and the AMG purred up a long driveway through extensive manicured gardens. With dawn painting the sky, scores of shabbily dressed men were already out pruning, sweeping and hosing. The driver negotiated an elaborate turning circle with a leaping bronze tiger fountain at its centre, and pulled up beside a flight of white marble steps that swept up to the house – if you could call it that, for Wijaya Suyanto’s residence was the third biggest in Indonesia, and its three storeys and 2000 square metres of decadent baroque opulence were testament to her father’s pervasive influence over four decades of corruption.

Angka stiffly held the car door open for Sura. Ignoring him, she got out of the car and made her way up the stairs to the vestibule where the skins of sixteen Balinese tigers carpeted the floor. Their heads mounted on the walls seemed to gape in surprise that extinction was the price of such excess. Reaching the inner courtyard, with its genuine Florentine marble fountains, she turned left and made her way to the inner sanctum, a soundproof room her father rarely left, and her mother was not permitted to enter. Sometimes, Sura wondered how the great man had ever found the time to breed.

As usual, he was working. The office was dominated by a huge photograph of her father standing arm in arm with the former president, Suharto, founder of the Golkar party, the leadership of which he aspired. As ever, her father was immaculate: jet-black hair combed to perfection across his box-like head, crisp tan uniform replete with campaign and medal ribbons, and a large solid gold

badge that proclaimed his name to the world. Wijaya meant ‘victorious’, and her father had made it his life’s business to live up to it.

‘Ah, there you are,’ he said. ‘What was so important that I had to reschedule my briefing?’

Feeling light-headed, Sura stepped up to his massive desk.

‘Father, I have something for you.’

When she passed him the display box, she realised her hands were shaking. The general ran his finger over his golden initials and raised a shrewd eyebrow.

‘It’s not even my birthday, Sura. What are you up to?’

‘Please just open it, Father.’

She held her breath as he beheld what lay inside.

‘Oh, these are absolutely splendid,’ he said. ‘Genuine first-rate examples. A Knight’s Cross and Totenkopf insignia in silver? This must have cost you a fortune.’

‘Look at the reverse, Father. The initials.’

A rare moment of surprise transformed his usually blank features.

‘M. H!’ he exclaimed. ‘No, I don’t believe it!’

Jumping to his feet, he went to the glass cabinet housing the most precious items of his extensive militaria collection: a Pour le Mérite awarded to an ace in Richthofen’s circus; a Victoria Cross from the horrors of the Somme. His most valuable item was a cutlass owned by Lord Nelson, valued at over half a million dollars. Sometimes, Sura thought her father’s obsession was driven by a compulsive need to vicariously possess the bravery of men. Despite his own medals and awards, the Bintang Sakti, Indonesia’s highest military award for valour, had eluded him in his fighting years.

‘Here we are.’

He reached in and retrieved an evil-looking dagger with a bulbous black handle. By far the most battered item in his collection, it was indisputably his favourite, for he had sourced it himself as a young lieutenant, when policing the border of Indonesia’s brand-new colonial possession. How a wizened old Papuan came to be walking around the jungle with an SS dagger in 1971 had been a family talking point ever since.

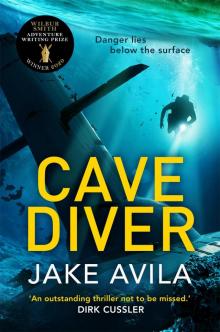

Cave Diver

Cave Diver